Gallipoli – The Naval Prelude

It’s easy for the casual visitor to Gallipoli, pressed for time and viewing things from a purely Australian perspective, to think that the campaign began as a deliberately planned amphibious operation at Anzac Cove. The ANZAC contribution was one part of the wider Dardanelles campaign – originally conceived as a naval attack to open the passage to the Sea of Marmara. This month we look at the beginning of the chain of events that saw a purely naval enterprise become a major, protracted and ill-fated land campaign.

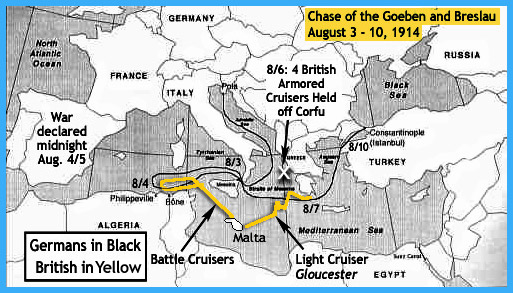

When war was declared on 4 August 1914 a series of maritime events occurred that was to have a direct effect on Turkey, still neutral but being courted both by the Allies and the Central Powers. Under the War Powers Act the Admiralty appropriated two battleships under construction in British shipyards for the Turkish navy. The appropriation outraged Turkish public opinion, the ships having been largely funded by public subscription. Seeing an opportunity, the Kaiser offered two ships of the Imperial German Navy’s Mediterranean Division as replacements. One of the ships, the Breslau, was a light cruiser but the other, SMS Goeben, was a modern, powerful battlecruiser.

Arriving off the Dardanelles on 10 August after twice evading a pursuing British cruiser squadron, the German ships were granted passage, contrary to neutrality laws, but entry was denied to their pursuers. British protests were answered with the claim that Turkey had purchased the two ships to replace the appropriated vessels. The final rupture of pre-war relations came on 15 August when control of the Turkish Navy was transferred from the resident British Naval Advisory Mission to the commander of the German flotilla.

When war was declared on 4 August 1914 a series of maritime events occurred that was to have a direct effect on Turkey, still neutral but being courted both by the Allies and the Central Powers. Under the War Powers Act the Admiralty appropriated two battleships under construction in British shipyards for the Turkish navy. The appropriation outraged Turkish public opinion, the ships having been largely funded by public subscription. Seeing an opportunity, the Kaiser offered two ships of the Imperial German Navy’s Mediterranean Division as replacements. One of the ships, the Breslau, was a light cruiser but the other, SMS Goeben, was a modern, powerful battlecruiser.

Arriving off the Dardanelles on 10 August after twice evading a pursuing British cruiser squadron, the German ships were granted passage, contrary to neutrality laws, but entry was denied to their pursuers. British protests were answered with the claim that Turkey had purchased the two ships to replace the appropriated vessels. The final rupture of pre-war relations came on 15 August when control of the Turkish Navy was transferred from the resident British Naval Advisory Mission to the commander of the German flotilla.

In the interval, on 3 November, on the orders of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, the blockading force shelled the Turkish fortifications at the entrance to the Dardanelles. While of no tactical advantage to the blockade, the action did focus Turkish attention on their vulnerabilities and led to a strengthening of the Dardanelles defences.

Various proposals for action against Turkey, or against Germany’s ally Austria-Hungary via the Balkans, were then considered but no decision was reached. In early January 1915 the Russians requested a diversion to relieve Turkish pressure in the Caucasus. With no British troops available, it was thought that the Royal Navy could mount a demonstration to divert Turkish reinforcements from the Caucasus. The place was to be the Dardanelles and the scene was set for the next step leading to the Gallipoli campaign.

Churchill queried Vice Admiral Carden, commanding the redesignated Eastern Mediterranean Squadron, regarding the forcing of the Dardanelles by seapower alone. Carden replied that a measured advance up the straits, progressively destroying the fortifications was required and listed the necessary resources, including additional ships. Of the various schemes for naval participation put forward by Churchill in the early months of the war this one was acceptable to the Admiralty. All but two of the ships being risked were old, pre-Dreadnought class vessels built around the turn of the century. The more modern ships of the Grand Fleet remained in home waters awaiting the decisive battle with the German High Seas Fleet. The plan was accepted by the War Council in mid January and Carden was directed to begin preparations. The only involvement of troops in the plan was a force to garrison positions reduced by the navy.

The first phase of Carden’s plan began on 19 February 1915. Units of the fleet, now including French and one Russian vessel, commenced fire on the outer fortifications from 12,000 yards range. Despite shortening the range, the limited number of large calibre guns on the old ships and a slow rate of fire provided no success by day’s end. Some Turkish guns were destroyed on 25 February, but it was not until demolition parties supported by marines were landed to blow up guns in the forts that had been shelled that results were achieved.

As the operation moved into March, the climactic naval action occurred that was to fundamentally change the campaign plan. We will look at these events in next month’s highlight.

Article written by Rod Margetts - who is a battlefield tour guide for Boronia Travel Centre.

Image Top Left: SMS Breslau. Source: Wikipedia.com

Image Middle: Chase of the Goeben and Breslau, August 3-10, 1914. Source: Cityofart.net

Image Bottom Right: The Goeben and Breslau at the Straits, Aug. 10, 1914 -- about to change the course of history. Source: Cityofart.net

In the interval, on 3 November, on the orders of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, the blockading force shelled the Turkish fortifications at the entrance to the Dardanelles. While of no tactical advantage to the blockade, the action did focus Turkish attention on their vulnerabilities and led to a strengthening of the Dardanelles defences.

Various proposals for action against Turkey, or against Germany’s ally Austria-Hungary via the Balkans, were then considered but no decision was reached. In early January 1915 the Russians requested a diversion to relieve Turkish pressure in the Caucasus. With no British troops available, it was thought that the Royal Navy could mount a demonstration to divert Turkish reinforcements from the Caucasus. The place was to be the Dardanelles and the scene was set for the next step leading to the Gallipoli campaign.

Churchill queried Vice Admiral Carden, commanding the redesignated Eastern Mediterranean Squadron, regarding the forcing of the Dardanelles by seapower alone. Carden replied that a measured advance up the straits, progressively destroying the fortifications was required and listed the necessary resources, including additional ships. Of the various schemes for naval participation put forward by Churchill in the early months of the war this one was acceptable to the Admiralty. All but two of the ships being risked were old, pre-Dreadnought class vessels built around the turn of the century. The more modern ships of the Grand Fleet remained in home waters awaiting the decisive battle with the German High Seas Fleet. The plan was accepted by the War Council in mid January and Carden was directed to begin preparations. The only involvement of troops in the plan was a force to garrison positions reduced by the navy.

The first phase of Carden’s plan began on 19 February 1915. Units of the fleet, now including French and one Russian vessel, commenced fire on the outer fortifications from 12,000 yards range. Despite shortening the range, the limited number of large calibre guns on the old ships and a slow rate of fire provided no success by day’s end. Some Turkish guns were destroyed on 25 February, but it was not until demolition parties supported by marines were landed to blow up guns in the forts that had been shelled that results were achieved.

As the operation moved into March, the climactic naval action occurred that was to fundamentally change the campaign plan. We will look at these events in next month’s highlight.

Article written by Rod Margetts - who is a battlefield tour guide for Boronia Travel Centre.

Image Top Left: SMS Breslau. Source: Wikipedia.com

Image Middle: Chase of the Goeben and Breslau, August 3-10, 1914. Source: Cityofart.net

Image Bottom Right: The Goeben and Breslau at the Straits, Aug. 10, 1914 -- about to change the course of history. Source: Cityofart.net

When war was declared on 4 August 1914 a series of maritime events occurred that was to have a direct effect on Turkey, still neutral but being courted both by the Allies and the Central Powers. Under the War Powers Act the Admiralty appropriated two battleships under construction in British shipyards for the Turkish navy. The appropriation outraged Turkish public opinion, the ships having been largely funded by public subscription. Seeing an opportunity, the Kaiser offered two ships of the Imperial German Navy’s Mediterranean Division as replacements. One of the ships, the Breslau, was a light cruiser but the other, SMS Goeben, was a modern, powerful battlecruiser.

Arriving off the Dardanelles on 10 August after twice evading a pursuing British cruiser squadron, the German ships were granted passage, contrary to neutrality laws, but entry was denied to their pursuers. British protests were answered with the claim that Turkey had purchased the two ships to replace the appropriated vessels. The final rupture of pre-war relations came on 15 August when control of the Turkish Navy was transferred from the resident British Naval Advisory Mission to the commander of the German flotilla.

When war was declared on 4 August 1914 a series of maritime events occurred that was to have a direct effect on Turkey, still neutral but being courted both by the Allies and the Central Powers. Under the War Powers Act the Admiralty appropriated two battleships under construction in British shipyards for the Turkish navy. The appropriation outraged Turkish public opinion, the ships having been largely funded by public subscription. Seeing an opportunity, the Kaiser offered two ships of the Imperial German Navy’s Mediterranean Division as replacements. One of the ships, the Breslau, was a light cruiser but the other, SMS Goeben, was a modern, powerful battlecruiser.

Arriving off the Dardanelles on 10 August after twice evading a pursuing British cruiser squadron, the German ships were granted passage, contrary to neutrality laws, but entry was denied to their pursuers. British protests were answered with the claim that Turkey had purchased the two ships to replace the appropriated vessels. The final rupture of pre-war relations came on 15 August when control of the Turkish Navy was transferred from the resident British Naval Advisory Mission to the commander of the German flotilla.

In the interval, on 3 November, on the orders of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, the blockading force shelled the Turkish fortifications at the entrance to the Dardanelles. While of no tactical advantage to the blockade, the action did focus Turkish attention on their vulnerabilities and led to a strengthening of the Dardanelles defences.

Various proposals for action against Turkey, or against Germany’s ally Austria-Hungary via the Balkans, were then considered but no decision was reached. In early January 1915 the Russians requested a diversion to relieve Turkish pressure in the Caucasus. With no British troops available, it was thought that the Royal Navy could mount a demonstration to divert Turkish reinforcements from the Caucasus. The place was to be the Dardanelles and the scene was set for the next step leading to the Gallipoli campaign.

Churchill queried Vice Admiral Carden, commanding the redesignated Eastern Mediterranean Squadron, regarding the forcing of the Dardanelles by seapower alone. Carden replied that a measured advance up the straits, progressively destroying the fortifications was required and listed the necessary resources, including additional ships. Of the various schemes for naval participation put forward by Churchill in the early months of the war this one was acceptable to the Admiralty. All but two of the ships being risked were old, pre-Dreadnought class vessels built around the turn of the century. The more modern ships of the Grand Fleet remained in home waters awaiting the decisive battle with the German High Seas Fleet. The plan was accepted by the War Council in mid January and Carden was directed to begin preparations. The only involvement of troops in the plan was a force to garrison positions reduced by the navy.

The first phase of Carden’s plan began on 19 February 1915. Units of the fleet, now including French and one Russian vessel, commenced fire on the outer fortifications from 12,000 yards range. Despite shortening the range, the limited number of large calibre guns on the old ships and a slow rate of fire provided no success by day’s end. Some Turkish guns were destroyed on 25 February, but it was not until demolition parties supported by marines were landed to blow up guns in the forts that had been shelled that results were achieved.

As the operation moved into March, the climactic naval action occurred that was to fundamentally change the campaign plan. We will look at these events in next month’s highlight.

Article written by Rod Margetts - who is a battlefield tour guide for Boronia Travel Centre.

Image Top Left: SMS Breslau. Source: Wikipedia.com

Image Middle: Chase of the Goeben and Breslau, August 3-10, 1914. Source: Cityofart.net

Image Bottom Right: The Goeben and Breslau at the Straits, Aug. 10, 1914 -- about to change the course of history. Source: Cityofart.net

In the interval, on 3 November, on the orders of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, the blockading force shelled the Turkish fortifications at the entrance to the Dardanelles. While of no tactical advantage to the blockade, the action did focus Turkish attention on their vulnerabilities and led to a strengthening of the Dardanelles defences.

Various proposals for action against Turkey, or against Germany’s ally Austria-Hungary via the Balkans, were then considered but no decision was reached. In early January 1915 the Russians requested a diversion to relieve Turkish pressure in the Caucasus. With no British troops available, it was thought that the Royal Navy could mount a demonstration to divert Turkish reinforcements from the Caucasus. The place was to be the Dardanelles and the scene was set for the next step leading to the Gallipoli campaign.

Churchill queried Vice Admiral Carden, commanding the redesignated Eastern Mediterranean Squadron, regarding the forcing of the Dardanelles by seapower alone. Carden replied that a measured advance up the straits, progressively destroying the fortifications was required and listed the necessary resources, including additional ships. Of the various schemes for naval participation put forward by Churchill in the early months of the war this one was acceptable to the Admiralty. All but two of the ships being risked were old, pre-Dreadnought class vessels built around the turn of the century. The more modern ships of the Grand Fleet remained in home waters awaiting the decisive battle with the German High Seas Fleet. The plan was accepted by the War Council in mid January and Carden was directed to begin preparations. The only involvement of troops in the plan was a force to garrison positions reduced by the navy.

The first phase of Carden’s plan began on 19 February 1915. Units of the fleet, now including French and one Russian vessel, commenced fire on the outer fortifications from 12,000 yards range. Despite shortening the range, the limited number of large calibre guns on the old ships and a slow rate of fire provided no success by day’s end. Some Turkish guns were destroyed on 25 February, but it was not until demolition parties supported by marines were landed to blow up guns in the forts that had been shelled that results were achieved.

As the operation moved into March, the climactic naval action occurred that was to fundamentally change the campaign plan. We will look at these events in next month’s highlight.

Article written by Rod Margetts - who is a battlefield tour guide for Boronia Travel Centre.

Image Top Left: SMS Breslau. Source: Wikipedia.com

Image Middle: Chase of the Goeben and Breslau, August 3-10, 1914. Source: Cityofart.net

Image Bottom Right: The Goeben and Breslau at the Straits, Aug. 10, 1914 -- about to change the course of history. Source: Cityofart.net

This entry was posted in Historical Highlights. Bookmark the permalink.